Electric vehicles (EVs) are catching on faster than even

their most ardent supporters ever expected, which inevitably means the pile of

spent lithium-ion batteries that once powered those cars is also rising fast.

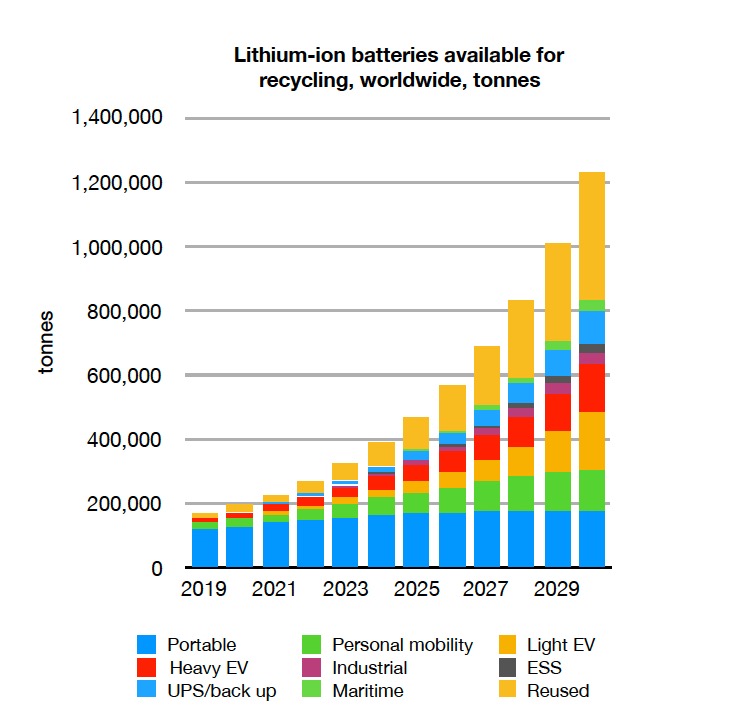

China alone is forecast to generate around 500,000 tonnes of

battery waste by 2020, a number that would hit 1.2 million tonnes per year

by 2030, when considering global consumption, London-based Circular Energy

Storage (CES) said Thursday.

Some companies, such as tech giant Apple, are grabbing the bull by the horns by trying to re-use as many minerals contained in discarded batteries as possible.

125,000 tonnes of lithium, 35,000 of cobalt and 86,000 of nickel could be recovered by 2030 from waste batteries

Circular Energy Storage

CES sees a profitable business on battery recycling.

According to the consultancy, recycled material and second life batteries can

generate a market worth more than $6 billion, based on current metal prices.

The experts believe the amount of lithium and cobalt from recycled materials will be equivalent to about a half and a quarter respectively of today’s markets for the mined commodities.

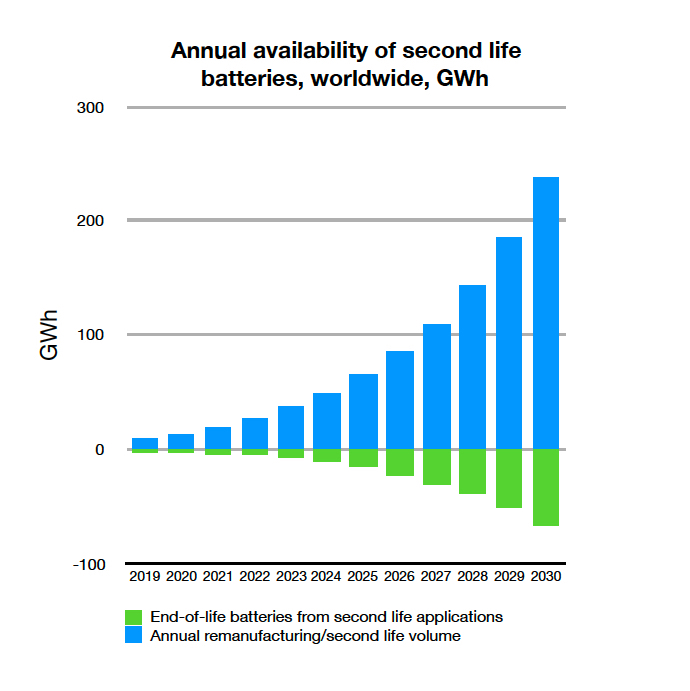

By 2030, they say, batteries with a capacity of close to 1,000 GWh will have become available for a second life, adding significant capacity to markets for backup power, stationary energy storage and EV charging.

“While the industry tend to focus on the electric cars we expect more batteries from heavy use applications such as electric buses, trucks, fork lifts, e-bikes and scooters,” says Hans Eric Melin, managing director at Circular Energy Storage and the author of the study. “However, the geographical differences are huge, both regarding volume and the characteristics of the waste stream.”

In North America and Europe, recycling is seen as a waste disposal activity that companies should be paid to carry out. In China, the largest producer and consumer of lithium-ion batteries, competition has become so intense that recyclers are willing to pay to get their hands on dead batteries.

This appetite means China’s grip on lithium-ion (Li-ion) battery recycling is set to grow. American and European recycling companies have good processes, but might struggle to find the volumes of used batteries needed for profitable operations.

One of the reasons, says Linda L. Gaines of Argonne National Laboratory, is that the Western world lacks a clear path to large-scale economical recycling, battery researchers say. As a consequence, manufacturers have traditionally focused on lowering costs and increasing battery longevity and charge, instead of trying to improve batteries’ recyclability. And because researchers have made only modest progress in that field, relatively few Li-ion batteries end up being recycled.

CES estimates that as much as 125,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE), 35,000 tonnes of cobalt and 86,000 tonnes of nickel could be recovered by 2030 from waste batteries. To this, between 400,000 and 1 million tonnes of production scrap might be added, depending on efficiency and production volume, it says.

“Together, processed volumes of waste lithium-ion batteries

and scrap materials will make up a market worth more than $6 billion,” the

consultancy predicts.

An even larger market is the one for remanufactured and second life batteries. CES anticipates that 75% of light, heavy and utility vehicle batteries will either be remanufactured for use in its original applications, or repurposed to be used in other stationary energy storage systems.