The Global Tailings Review, an initiative launched following the tragedy at Vale’s Corrego do Feijão mine in Brazil early this year, has kicked off a six-week public consultation on a draft of global standards to improve mine safety.

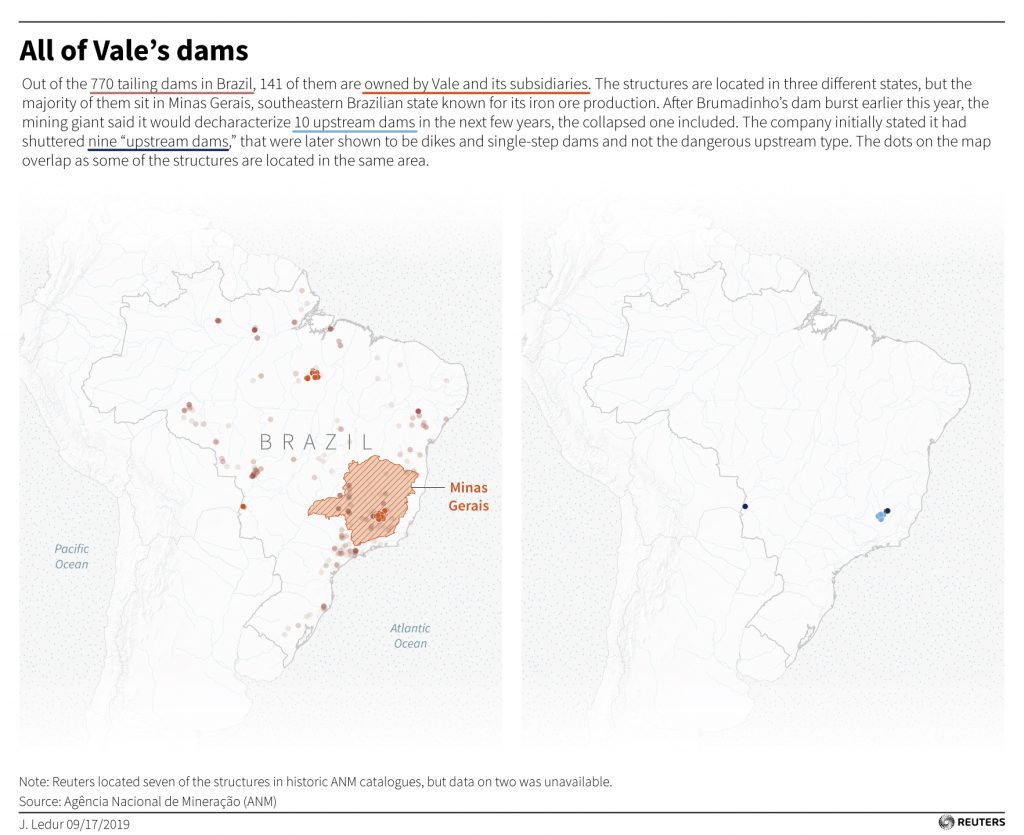

The push for worldwide rules governing the construction and maintenance of mining waste storage facilities aims to prevent any repeat of the tailings dam disaster that in January hit the state of Minas Gerais, for the second time in four years, and which killed 300 people.

The review, backed by the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), has been in the works since March this year.

The ultimate goal is to prevent a repeat of Vale’s tailings dam burst in January, which killed 300 people

The ICMM, a London-based industry group representing 27 major mining companies, had vowed earlier to set an independent panel of experts in charge of developing global standards for tailings facilities.

The goal, according to expert Bruno

Oberle, who is chairing the review, is to decide on standards to be published

in 2020.

“The public consultation phase allows for critique, feedback and suggestions from others that both informs and enriches the draft, he said in a statement.

Oberle noted that the document was part

of a wider global drive to strengthen performance on tailings management, adding

that the requirements of the draft could complement such initiatives.

The consultation he leads includes an online survey that has been translated into seven languages.

A parallel global inquiry into mining waste storage systems of more than 700 resources companies, launched in April by the Church of England (CoE) and fund managers, recently revealed that about a tenth of those structures have had stability issues.

Those results, however, are

considered partial, as they only reflect disclosures from less than half

of the 726 companies contacted following Brumadinho dam’s collapse.

Currently there is no set of universal rules defining exactly what a tailings dam is, how to build one and how to care for it after it is decommissioned.

Some previous effort in that

direction includes the World Mine Tailings Failures, an online database that aims

at exposing the cause of tailing dams disasters, giving direction on how to

prevent them.

There are about 3,500 tailings dams

around the world. Unlike the ones used to build reservoirs or hydroelectric

projects, tailings dams are not usually made from reinforced concrete or stone.

They are mostly constructed from the waste material left over from mining

operations, which — depending on the type of mine — can be toxic.

Only three countries in the world ban upstream dams — Chile, Peru and now Brazil. Chile, the world’s No.1 copper producer, also regulates the minimum distance between dams and urban centres. But the nation still has 740 tailings deposits, only 101 of which are active, with the rest abandoned or inactive, according to data from mining agency Sernageomin.

If adopted by miners and governments, the standards recommended by the Global Tailings Review would require companies to design and monitor their dams to new, tougher benchmarks.

They would also demand greater public disclosure about the facilities and, especially, prohibit any conflicts of interest between companies and safety inspectors.